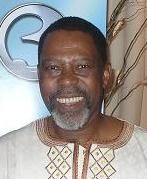

The Golden Plumes introduced me to Professor Mbulelo Mzamane, a man that I am very proud to share a first name with! His speech at the awards taught me a lot about how Television started in SA and being passionate about Mzansi TV, I concur with the saying that goes "for you to know where you are going, you have to know where you come from" and this is where the SABC comes from, where it is and I hope we have a say as to where it is going!

BIOGRAPHY:

Mbulelo Vizikhungo Mzamane, first post-apartheid Vice Chancellor and Rector at the University of Fort Hare, has taught English Studies, Comparative Literature, and African Studies at universities in Southern Africa, West Africa, Europe, US, and Australia.

Mzamane was appointed by former President Nelson Mandela and current President Thabo Mbeki to serve on the SABC Board and the Heraldry Council. He was for eight years founder chairman of the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism, the founding patron of the Freedom of Expression Institute, and the founding director of the Book Development Council of Africa.

He is currently engaged in producing, under the auspices of the national Department of Arts and Culture, an Encyclopaedia of South African Arts and Culture.

Check out his full profile here

Ok, now that you've checked him out, here is the speech that blew us away and remember, you can catch him and all the other peeps who have kept us glued to our screens for the past 30 Years, on Friday, 22 December 2006 at 20:00 on SABC 3!

Celebrating Thirty Years of Television in South Africa

by Mbulelo Vizikhungo Mzamane

I am gratified by the fact that there is no one in this audience so young as not to remember when there was no television in South Africa! Television then was regarded as the devil’s own box for disseminating communism and immorality – even if, their treasonable hormones running riot like those of overgrown teenage kinders, dominees of the Dutch Reformed Church (known in my time as the National Party at prayer) broke the Immorality Act with gleeful impunity and without assistance from television. We have traversed some distances since those dark days when we experienced sunset at midday; and we have forded many streams on the road to democracy.

I want to invite you to come with me down memory lane to look at some landmarks and milestones on our long walk to freedom of expression, lest in our euphoria tonight we forget and become struck by some collective amnesia like most of South Africa today. My brief this evening is not to pull any punches, so fasten your seat belts. And because I am an African but I do not owe my being to anyone of you, I intend to speak my native mind and I can parody anyone I like.

These are essential freedoms, like the air I breathe, for which as a creative writer I fought to be free of any restrictions that are extraneous to the creative process and the pursuit of Truth.

The SABC became the ideological repository of and chief apologist for Apartheid, offering a broadcasting policy characterised by an unabashedly pro-government stance and programming for the white majority. It was dominated by its controller for twenty years and chief imbongi or cheer leader Piet Meyer, who remained a full-blown Nazi until his death. During the 1930s, many bright young Afrikaners went to Europe to study. There, they were inspired by fascism which was gaining popularity in Spain, Italy, Portugal and, notably, Germany. Afrikaner intellectuals began to use the word Apartheid during this period. Among those who studied in Germany were Hendrik Verwoerd, prime minister of South Africa from 1958 to 1966, and Piet Meyer.

Those who worked for the corporation in the Piet Meyer era – long before Dali Mpofu and Snuki Zikalala – testify to the fact that progress within the corporation then depended entirely on one’s political credentials. I have vivid recollections of Piet Meyer advising the defendants in the Rivonia Trial facing the death sentence to begin making peace with their maker! There was nothing then like innocent-till-proven-guilty for enemies of the state.

South Africans were allowed to watch television only from the last quarter of the 20th century. It was used then primarily as a propaganda machine, as I have said. But let us fast forward to 1995. The camera zooms in on Nelson Mandela standing on the field in a packed stadium. He is wearing a number six jersey instead of his customary Madiba shirts. His fist is clenched, not in the black power salute but, in triumph as Francois Pienaar alongside him lifts the Webb Ellis trophy into the sky. For a few short moments South Africans in their lounges, pubs and shebeens are euphoric. This power to grip the public's attention, to reflect and shape a national consciousness, and to help create its mythologies makes television the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor and liberator alike.

And yet for all its persuasiveness and power, TV had a relatively late South African debut and was only introduced to the country on January 5, 1976, after a protracted, sometimes painful, and often comic debate. Television had long been opposed by the Minister of Posts and Telegraphs, Dr Albert Hertzog, on the grounds that, among other things, it showed blacks and whites living together. Plans for television only went through when John Vorster, prime minister from 1966 to 1978, dropped Hertzog from the cabinet in 1968. On the eve of its introduction, Hertzog predicted spiritual doom and moral degradation unless the "evil is rooted out".

But if television was late in coming to South Africa, there was nothing tardy about the way the state set about securing control of the new medium. In fact, the National Party began soon after they came to power in 1948 to install their apparatchiks in the SABC. The SABC of 1948 was a child of the British Broadcasting Corporation. Back in 1936, General JBM Hertzog as prime minister invited the BBC's founder, Lord John Reith, to suggest how South Africa's fledgling broadcasting service, at that time commercially run, could be developed. And the SABC virtually adopted the BBC's Royal Charter, in effect committing itself to a liberal policy and a degree of independence from the state. However, in 1958, Albert Hertzog, who must have had a love-hate relationship with his father General Hertzog, was appointed Posts and Telegraphs Minister and things began to change apace as he set out with diabolical genius to undo his father’s legacy.

ONE of Albert Hertzog's first acts as minister was to invite his friend Piet Meyer to take over the chairmanship of the SABC. Meyer was to remain head of the broadcaster until 1980. Significantly, in 1960 Meyer also became chairman of the Broederbond, set up to advance the interests of Afrikanerdom. Meyer had firm ideas about the role the SABC should play in the life of the nation, as he was to explain to the general council of the Broederbond in 1977: "We must harness all our communication media in a positive way in order to gather up Afrikaner national political energy in the struggle for survival in the future ... Our members must play a leading role!"

The first casualty under Meyer's reign was the SABC's director-general, Gideon Roos. Despite being a pioneer of Afrikaans broadcasting and a fervent supporter of the NP, Roos was an obstacle to Meyer's designs because he saw the broadcaster's role as a reporter, not as a propagandist. Roos' powers were whittled away and he finally resigned in 1961 when Meyer, who had stacked the board with broeders, announced the SABC would have its own editorial policy.

In 1978, the Sunday Times revealed that at least four of the nine members on the SABC's board of management were members of the Broederbond. The SABC's director-general and a leading broeder around that time, Douglas Fuchs, is on record as saying: "We are involved in the politics of survival. The SABC cannot stand aside." The role of the South African broadcaster, he maintained, was to report on positive achievement, to prevent dissension among South Africa's "different nations", and to counteract the "negative criticism" of the English language press and of the outside world. "We cannot cast doubt on the rulers of the country. No useful purpose can be served by causing the public distrust of our leaders' policies," Fuchs said.

In only its second month of fulltime broadcasting, the SABC in March 1976 introduced political commentary in the middle of television news. Head of SABC television news and commentary, Kobus Hamman, claimed at the time that SABC commentators were "from all sorts of political persuasions". Commentaries were intended to explain the news, he added, not to indoctrinate. This was patently not the case, however, as was confirmed to journalist Marshall Lee when he once asked an SABC senior political commentator, Alexander Steward, why "Current Affairs" never deviated from the government line. Would not the message carry more conviction if there were occasional criticism of Pretoria's mistakes? Lee enquired. "By asking that it shows you do not understand the ways of propaganda,” Steward said. “With propaganda you never let up."

IN 1978, PW Botha was elected prime minister after ousting his rivals in the wake of the Info Scandal. This was a scandal which coincidentally turned on the state's manipulation of the media – or, more precisely, the state's extra-parliamentary use of public money to acquire its own voice in the English language press. The Citizen newspaper is a legacy of those troubled times. But for all that, the Botha regime, like its successor under De Klerk, had no qualms about continuing the state's manipulation of the SABC.

Botha's election coincided with a period of increasing turmoil in South Africa and on the country's "borders". Colonialism was unravelling in Africa. Former colonies, especially Angola and Mozambique, had recently become independent. The involvement of South Africa's industrial-military complex in South West Africa (Namibia to its people) and neighbouring countries was deepening. The SADF was suffering casualties from its incursions into Angola. Turmoil gripped the townships following the Soweto uprising of 1976. The black trade union movement was beginning to flex its muscles. A culture of “siyayinyova” (or ungovernability) was becoming implanted that twelve years into our democracy we are still failing to uproot altogether.

Economic, sporting and cultural sanctions were intensifying. Foreign capital was fleeing. But that was not exactly what confronted South Africans who turned to the national mirror. British broadcaster and author David Harrison, reflecting on the period, points out that under the broadcasting broeders: "No minister can officiate at the opening of a dam or power station without the attentive presence of an SABC camera." TV images of the prime minister and cabinet ministers visiting homeland states and being received by "grinning acolytes and singing children" predominated. The true extent and nature of South Africa's foreign military entanglements was also never revealed by the national broadcaster. As Govan Mbeki recalled in 1996:

The state security system identified the cause of the country's woes as an onslaught by the communists from the north. The red peril that was to overtake the country became the focus of TV propaganda on a nightly basis. The white population was brainwashed into accepting that the government's security apparatus was the only hope of salvation from evil communists.

Safe foreign guests were interviewed at length on TV while even the mildest critics of the regime like Helen Suzman could only expect tightly edited snippets – allowing the SABC to maintain at least a facade of objectivity. Suzman's fellow parliamentarian and leader of the Progressive Federal Party, Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, in his 1985 memoir, The Last White Parliament, sketches how the NP fostered a perception of a significant right-wing threat as a way to buttress the moderate white vote. He wrote: "A cabinet minister laughingly told me: 'Come election time, all we do is show Eugene Terre'blanche giving his Nazi salute on TV and your voters will flock to our tables in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg'." The 1983 referendum for a tricameral parliament, van Zyl Slabbert continues, "was also the first time that the government had manipulated television and the radio bluntly and shamelessly as part of their marketing campaign. In fact a senior National Party MP told me how a group of them would get together every day and plan what was going to be shown from all parties that evening." Van Zyl Slabbert defines the period as one of declining information and increasing disinformation. Vilification for acts of terrorism from the one side and praise and glorification for the other was the order of the day as both the state and the liberation movements engaged in propaganda warfare – this is the continuing battle by some other means to which I would like to return at the end for the heart and soul and mind of South Africa.

HOWEVER, while the NP from the early- to mid-1980s increasingly talked a hard line and warned on TV of a “Total Onslaught” and reds under the bed, the period was also one of relative pragmatism and much touted reform. Influx control was scrapped, prohibitions on inter-race marriages were repealed, and black trade unions were made legal. The NP also eased, somewhat, their stranglehold on TV. Graham Leach, a BBC correspondent in South Africa at the time, writes that perhaps Botha's greatest achievement was to change the political debate in South Africa from one concerned with how to keep blacks out to one focused on how to bring them in. He reckoned it was better to have blacks inside the tent peeing outside than to have them outside peeing inside.

A nightly current affairs programme, Network, which included lively debate and anti-government views from the likes of Jesse Jackson, was launched in 1985. Lee further noted that, “Apartheid laws which threatened stability or whose abolition might help buy more time were quickly dispensed with." But as the political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville reminds us: "The most perilous moment for a bad government is when it seeks to mend its ways ... (since) a grievance comes to appear intolerable once the possibility of removing it crosses men's minds."

And so it was that when PW Botha's fateful Rubicon speech was broadcast, it sparked an economic crisis. Violence had exploded once again in the townships and successive states of emergency were called. The government's limited commitment to black participation was the first casualty of the violence; the second was freedom of expression and programmes like Network, where the political reporters and interviewers were suddenly changed. Television and radio reporting were subject to restrictions. News that related to "unrest" and to the actions of the security forces was supplied by the Bureau for (Dis) Information. After lambasting foreign correspondents for "paying" blacks to incite unrest – as if Apartheid was not incitement enough – PW Botha barred all camera teams from troubled areas. All information regarding the war in the townships was issued by the police.

The 1980s drew to a close with Botha seeming to lack the vision to finish the job he had started. The country was becoming a military state with securocrats increasingly having a hand in the day-to-day administration of the country. But then fate stepped in. In January, 1989, Botha suffered a stroke. A palace revolt followed and in August the president recorded a television address announcing his resignation. Six months after his inauguration President Frederik Willem de Klerk in his opening of parliament address, televised to an audience of millions, announced, on February 2, 1990, the unbanning of the liberation movements and imminent release of Nelson Mandela.

I cite these precedents in order to hold a mirror to our post-Apartheid era and take note that those who refuse to learn from history are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. And South Africans are most adept at that. You want to learn to be your own self’s worst critic in order to revalidate a South African truism that, as poet laureate and imbongi yesizwe jikelele Keorapetse Kgositsile says: “Truth cannot be enslaved in an Island Inferno”. You also want to learn, as award winning author Njabulo Ndebele, says: “It is a blind progeny that acts without proper indebtedness to the past.”

AND so we return to 1995 and the televised-around-the-world image of Mandela celebrating with the bokke at Ellis Park. We are now in an era where the themes which predominate on TV are nation-building and reconciliation. The socialist rhetoric and radicalism of the pre-'94 period no longer sit well with South Africa's dominant black interest groups. The concern now is to transfer economic power to a specific group, not to destroy capitalism. Leading trade unionists have become leading captains of industry, and media moguls to boot. Cyril Ramaphosa chaired telecom and media conglomerate Johnnic (which holds a significant stake in pay channel MNet and its sibling company Supersport), while former trade union leader Marcel Goulding became chief executive officer of e.tv (the Warner Brothers-backed free-to-air television company).

But while there is some controversy as to whether these two groups are indeed the black empowerment vehicles they purport to be, the battle for the hearts and minds of viewers continues. Witness the furore which surrounded the broadcasting of a documentary made by John Pilger which stripped some of the PR and media-manufactured shine off the New South Africa. The documentary, Apartheid Did Not Die, which argued the ANC had betrayed its cause, was broadcast only after much hand-wringing and was accompanied for reason of "balance" with a disclaimer and a panel discussion. Witness, too, the most recent furore about which political commentators are more kosher.

Talk of Pilger leads inevitably to Pilger's ideological mentor - Noam Chomsky, a stern critic of the West's brand of freedom. In a free society such as the new South Africa, do television and the media serve to replace coercion with indoctrination: feeding the yearnings of the millions while in reality only the aspirations of a tiny elite are advanced? Do the state broadcaster and its commercial counterparts, MNet and e.tv, exist to, in Walter Lippman's words, manufacture consent and a putative common sense of nationhood?

I have had the good fortune to be associated with the national broadcaster in its transformative years. I have vivid recollections of the appointment of the first representative SABC board in 1993 by the transitional government still led by FW de Klerk. Several of us from the darker side were nominated to serve on the new board and Njabulo Ndebele was proposed as chairperson. De Klerk objected on the grounds that Njabulo Ndebele was not bilingual – despite the fact that Njabulo Ndebele speaks and understands no less than nine of South Africa’s official languages while De Klerk is so linguistically challenged he can hardly say: “Molweni!”

This brings us to one of the most democratising policies the SABC adopted – and I am mightily proud to have been at the heart of the process as a member of the board’s language policy. Potentially one of the most empowering policy decisions to which I will come back at the end, the state’s and the SABC language policy is essential to deepening mass democratic participation, education and development, intra-African communication, and Africanising colonised minds in this country.

During my tenure at the SABC as a board member the corporation, under Zwelakhe Sisulu, embarked on several other policy options – notably (a) to right size the corporation but in reality to rid it of deadwood and (b) to align personnel with the country’s demographic features in gender, race and (dis)ability terms. Neither process ever satisfies everyone. The policy to bring in under-represented groups was decried as racism in reverse. I was privileged to sit on a commission that investigated complaints of heavy handedness and incompetence levelled against the new black political “commissars”. And when our commission that also included Paulos Zulu, Masepeke Sekhukhuni, and the late Dr Gabriel Setiloane could find no convincing evidence of black listing (as in listing blacks in favour of whites) the commercial press denounced our findings as little more than white-wash. EMzansi people still refuse to see things in colour – we are a rainbow nation only in name (besides the rainbow has no black in it) – we see things only in black-and-white.

Three significant factors that no one dared comment upon openly however emerged from the commission and gave me considerable insights into the workings of the corporation, if not the beloved country. First, there was fierce contestation and reluctance from previously privileged groupings to relinquish control of the news room (where real power resides) and these groupings were wont to use freedoms guaranteed all South Africans by the constitution cynically to undermine the aspirations of the under-represented majority. Second, there was contempt in some white quarters inside and outside the corporation for black leadership, contempt masquerading outrageously as “concern over falling standards”, without anyone ever explaining whose standards were being compromised. Third, as the SABC emerged as the voice of the voiceless (and sometimes and inevitably of the government that speaks for the voiceless) the commercial press (largely white) became quite naturally the last bastions and defenders of white hegemony. CLR James was correct to observe that, “Those in power never give way and admit defeat only to plot and scheme to regain their lost power and privilege.”

On to this scene came Barney Pityana and the Human Rights Commission. The media, like business and the judiciary, had tried to wait until the storm passed that had been raked up by the TRC’s call to the nation’s institutions to account for its role in maintaining oppressive structures. Philip van Niekerk led the charge in decrying “racism in reverse” and “witch hunts” initiated by the Human Rights Commission seeking answers to questions many South Africans continue to ask about the culpability of the media, business and the judiciary in maintaining and enforcing oppressive structures. My conclusion: there is inevitable competition that is not about to go away between the national broadcaster and the print media in particular; it is more about point-scoring than about corrective action and the pursuit of Truth.

The public broadcaster has, indeed, come a long way since the days of Piet Meyer of blessed memory. The major achievements have been in terms of reversing the legacy of Apartheid – that is the only “reverse” I see – and implanting the new ethos that promotes democracy, non-racism, non-sexism, and non-discrimination. SABC board and staff members since the advent of democracy come from every political spectrum – in my time we even had some board members with no particular political pedigree, a very rare phenomenon for any South African nurtured in the Piet Meyer era. In the case of Francois Beukman, he resigned his seat on the board to better serve the National Party in parliament. It is true that some had impeccable struggle credentials, while others were sprung from Apartheid culture. But as trustees of the corporation we learnt to leave our political colours outside the board room. And I worked happily with ATKV’s Fitz Kok to hammer out language policies that have since become the common sense of our age.

The other truly impressive accomplishment has been lowering the Apartheid curtain north of the Limpopo River and reaching to the heart of Africa. SABC-Africa, my favourite brand in this regard, as a Pan African proposition is an instrument of liberating our minds from their Western shackles and reintegrating us to the rest of the continent. We have also progressed in many other ways great and small that must surely make Piet Meyer, who would not survive a day at the helm of the SABC today, turn in his grave. But major challenges remain as in any other institution that is older than the new democratic order.

To mention some of the challenges that still confront the SABC is not to belittle the phenomenal gains but self-criticism is always a sure sign of maturity.

1. One of the most important challenges in my view that confront the national broadcaster is professional development – and I do not mean week-long courses that only serve to entrench half-literacy and incompetence. I have been at pains to engage Dali Mpofu and his predecessors, Zwelakhe Sisulu and Peter Matlare, to release staff for post-graduate programmes in broadcast journalism, information technology etc. We cannot be content to replace illiteracy with half-literacy. I have still to read a single Honours’, Masters or doctoral thesis written by an SABC employee on staff development. Where does your research and analysis come from? You are doomed to kick out unreconstructed bums and re-engage them as consultants and experts, if no internal mechanisms exist to churn out expertise. Erudition enables you to replace ignorance and arrogance, irrespective of their colour, with dry intellectual gun-powder and muskets that fire with efficiency. The SABC is the supreme educator and informer of them all. But you cannot inform if you are yourself ill-informed, in the same way that you can’t educate if you are yourself scared of being educated. Where are SABC scholarships to educate screen writers at university level instead of relying on natural born hustlers like some of my friends in the industry?

2. Second, the other challenging element the corporation faces, which I have already touched upon and I will not elaborate, is extending the benefits of African language broadcasting to the most linguistically marginalised groups – and not simply in token terms. African languages are an African renaissance imperative.

3. Third, we may have produced pioneering soapies in Mfundi Vundla’s “Generation” and Duma Ndlovu’s “Muvhango”. But local is anything but lekker. Programming at the lowest common denominator for the intellectually challenged is what largely passes for local content. I also see your Content Hub, a wonderful idea on paper, hobbling in no particular direction. It has held a most promising workshop on adaptation of African literary works for television but is failing to follow through on its earlier promise, thus losing momentum and enthusiasm earlier generated. Gestures and postures are no substitute for substance. The truth is that no local novel, for example, has been dramatised for television since Ityala Lamawele, Ingqumbo Yeminyanya, and Kwazidenge that were all done before 1994. Yet those programmes were only rivalled by the news in isiNguni in pulling sleepy audiences.

They proved beyond reasonable doubt the viability and sustainability of adapting popular novels for television. When I teach literature in the US, Australia, Europe, Nigeria or Senegal I can fall back on the resources of film and television to enable my students to visualise works by Charles Dickens, Leo Tolstoy, Emile Zola, and John Steinbeck, Chinua Achebe, and Sembene Ousmane – even African-American works such as The Invisible Man, Black Boy, A Dream Deferred etc. Where are similar adaptations of the works of our national literary treasures such as Peter Abrahams, Andre Brink, Nadine Gordimer, Bessie Head, Alex La Guma, Ephraim Lesoro, Zakes Mda, James Moiloa, Es’kia Mphahlele, Lauretta Ngcobo, Sibusiso Nyembezi, and Karel Schoeman? Why is the public broadcaster short-changing the South African child, for that is who gets culturally and intellectually stunted in the end? The Content Hub and others charged with the responsibility must eschew paralysis by analysis in the manner of most of our institutions, and go beyond good intentions.

4. Fifth, having successfully dislodged Apartheid apparatchiks form the SABC, the new democratic order wants to be careful not to replace them with its own apparatchiks. I need say no more on the matter that is the principal responsibility of the SABC board as representatives of the entire rainbow spectrum of the new South Africa.

5. Finally – and I have few illusions about this – the battle for the heart and soul and mind of South Africa continues; and it will be lost or won in the newsrooms and studios of the SABC.

If there are contradictions in some of my formulations – and I am certain there are some – it is the duty of the SABC board and management to reconcile them so that thirty years from now we can in fact celebrate our win-win situation in our living rooms, pubs and shebeens. In the final analysis, as Aime Cesaire points out, “there is no monopoly to truth and beauty; and there is room for us all at the rendezvous of victory.”

In conclusion, I want to add my voice in congratulating some truly pioneering figures we have come to honour, whom I am proud to call my friends from the trenches. Duma Ndlovu for producing the first Tshivenda soapie that is not Tshivenda; Mfundi Vundla for producing the first popular local soapie that is not so popular anymore; Marcel Goulding for the first free-to-air station; Koos Bekker of Naspers and MTN for keeping us fixated on other cultures; and all the others who in the past thirty years have brought us to where we are today.

Ends

All together now.....*clap*clap*clap*